Sophie Polo Behind the scenes of the X chromosome: how to repair broken DNA

Inserm researcher and head of the “Epigenome integrity” group at the Epigenetics and Cell Fate Centre - Université Paris Cité, Paris

- 2025 • Impulscience

Chromosomes, the guardians of our genetic identity, suffer damage that can compromise the health and fate of cells. Among these, double-strand DNA breaks are among the most critical. Sophie Polo is interested in how cells repair these breaks by studying a phenomenon unique to female mammals: X chromosome inactivation.

DNA, a structure that is both flexible and vulnerable

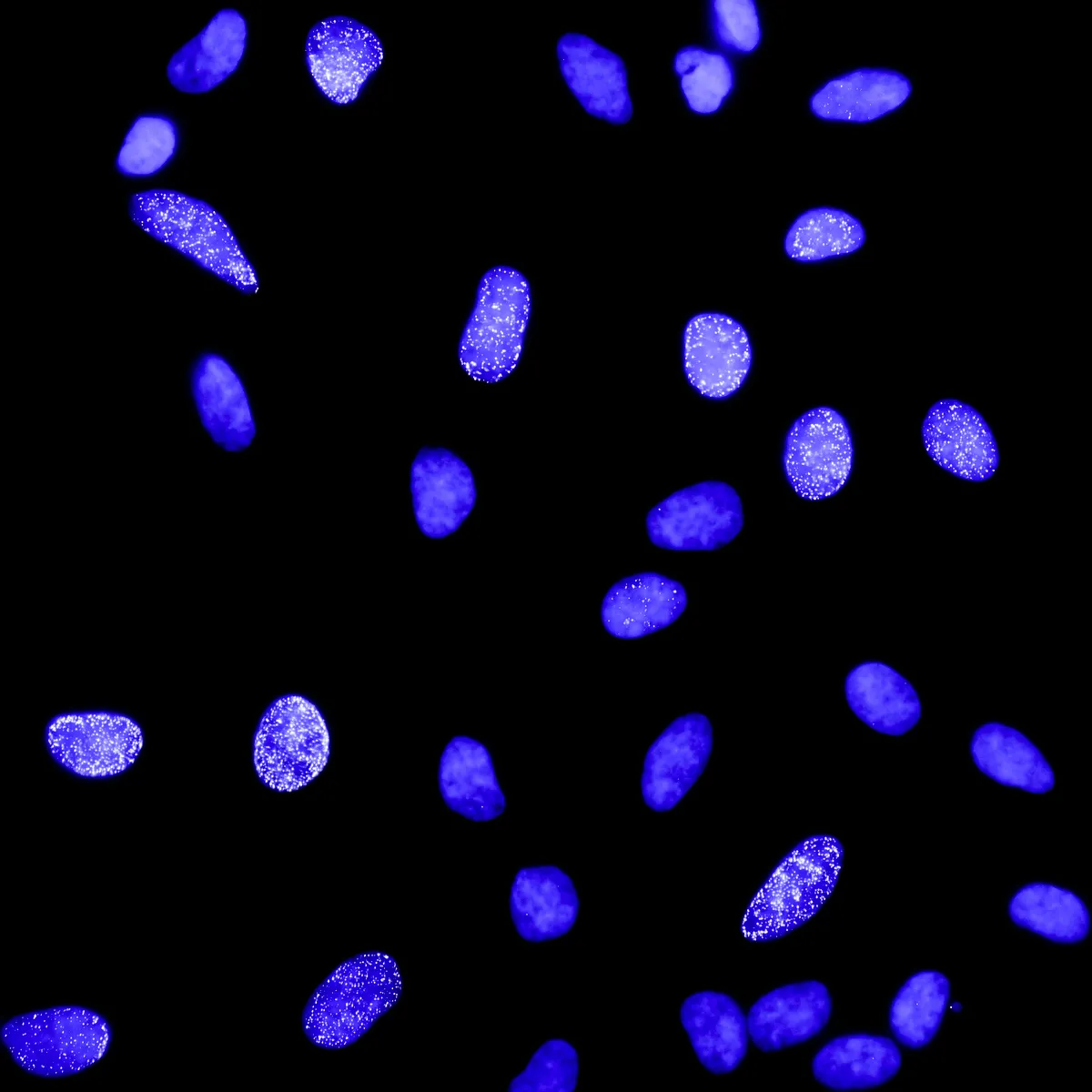

In the cell nucleus, genetic material is organised in the form of chromatin: an assembly of DNA and proteins called histones. This structure ensures both the stability and flexibility of DNA, allowing certain genes to be activated or deactivated according to the cell's needs.

Despite this sophisticated organisation, DNA remains fragile. It can suffer and sustain breaks, particularly those known as “double-strand breaks” which affect both strands of DNA, triggering repair mechanisms. The way in which chromatin is structured plays a crucial role in this repair process.

Facultative heterochromatin: chromatin unlike any other

Chromatin can take several forms: euchromatin, which has a generally decondensed structure that allows gene expression, and heterochromatin, which is the densest and most compact form. Heterochromatin is said to be “silent” or inactive because it prevents gene expression. This type of chromatin can be used in the cell on a temporary basis to regulate gene expression in an facultative manner, making it particularly important in embryonic development and in protecting cells against diseases such as cancer or autoimmune diseases.

A special case of this type of facultative heterochromatin is the inactivation of the X chromosome in female mammalian cells. They have two X chromosomes, and one of the two is rendered inactive at the beginning of embryonic development to avoid a double dose of the genes present on this chromosome. This inactive X chromosome remains silent throughout life. Despite the high frequency of DNA breaks in the inactive X chromosome, very little is known about how it responds to DNA breaks and influences their repair.

The X chromosome and the secrets of its inactivation

The Impulscience project led by Sophie Polo aims to shed light on the mechanisms of DNA repair in the inactive X chromosome. Using innovative strategies combining genome editing, imaging and proteomics, her team seeks to understand whether and how heterochromatin regulates the repair of double-strand DNA breaks. They will identify the changes in chromatin that accompany break repair and characterise the mechanisms that maintain X chromosome inactivation in response to breaks. Finally, they will examine the role of breaks in triggering X chromosome inactivation during embryonic development.

This project will provide unprecedented insight into the mechanisms of establishment and maintenance of X chromosome inactivation in response to DNA damage. This has important implications for understanding sex differences in disease susceptibility.

Sophie Polo in a few words

After graduating at the Ecole Normale Supérieure in Paris, she completed her PhD at the Institut Curie, where she studied the links between chromatin assembly, cell division and genome stability. She then pursued her research as a post-doctoral fellow at the Gurdon Institute in Cambridge (United Kingdom) in Sir Steve Jackson's laboratory and joined Inserm in 2011. In 2013, she founded the “Epigenome Integrity” group at Université Paris Cité, with the aim of deciphering the interactions between the genome and chromatin modifications, under both normal and pathological conditions.