Germán Sumbre Navigational strategies put to the test by evolution

Germán Sumbre, Inserm researcher, head of the “Neural Circuit dynamics & Behaviour” team at the Institut de Biologie de l’Ecole Normale Supérieure (IBENS), Paris

- 2025 • Impulscience

Animals navigate their environment thanks to their ability to assess their position in space, plan and execute a trajectory to reach a specific target. Using a highly unusual fish, Germán Sumbre and his team will study the evolution of brain computations, and more specifically how the representation of navigation in the brain evolves after drastic changes in the environment.

Integrating information to navigate the environment

To navigate in often complex environments, animals use different strategies based on external sensory information (e.g. light) and internal information (e.g. perception of body position). This data is integrated by precise neural networks in the brain to create cognitive spatial maps which function as an internal GPS, a compass and a pedometer, enabling animals to find their path and self-locate in space.

In fish, cues such as light, odours, water vibration and flow, sound, perception of body position and depth are essential for navigation. How is this external and internal information integrated in the brain to generate a mental representation of space? How do neural circuits evolve when the animal adapts to drastic environmental changes? Despite the existence of theoretical models, these mechanisms remain to be elucidated.

A cavefish to study navigation in changing environments

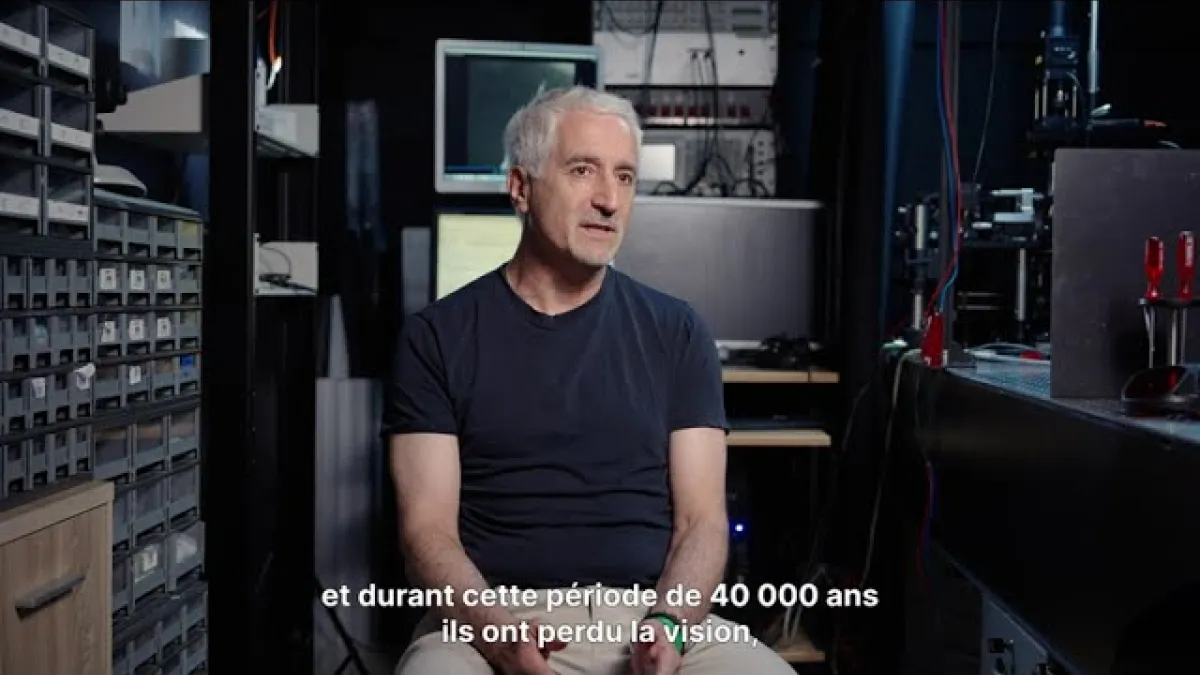

To address these questions, Germán Sumbre's team has chosen a fascinating study model: the fish Astyanax mexicanus, also known as the Mexican tetra. This species consists of river-dwelling fish and blind cave-dweller that were trapped in dark caves around 20,000 years ago. Confronted with radically different environmental conditions (darkness, scarcity of food sources, absence of predators) the cave fish developed numerous adaptations, including eyes loss, the disappearance of certain social behaviors, and the expansion of the water flow sensor (known as the lateral line). These evolutionary adaptations make Astyanax mexicanus a model of choice for studying the adaptation of neuronal circuits to the environment.

An innovative project to reveal the adaptation of spatial navigation mechanisms

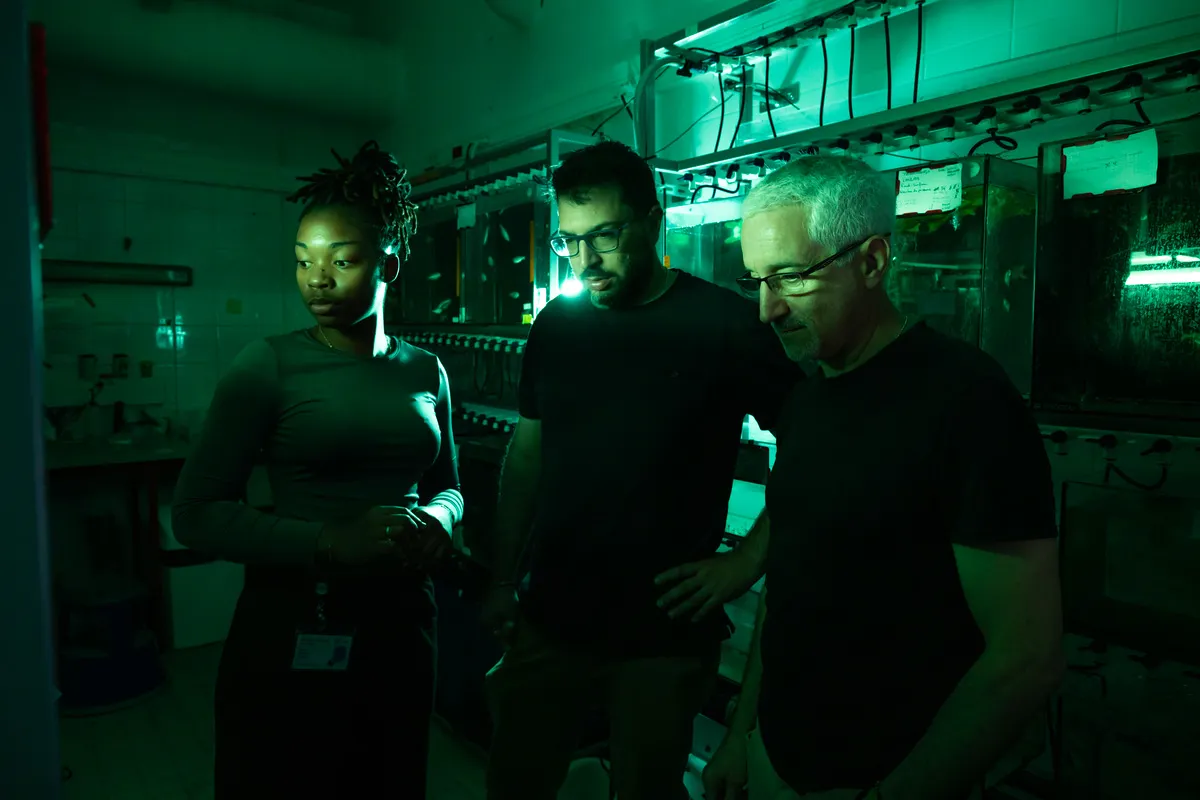

With the support of Impulscience®, Germán Sumbre and his team will mobilise their multidisciplinary expertise, developed over several years, to compare the navigational abilities and underlying neuronal circuits of two cave fish variants (which evolved independently in two separate caves) and the river variant of the same species.

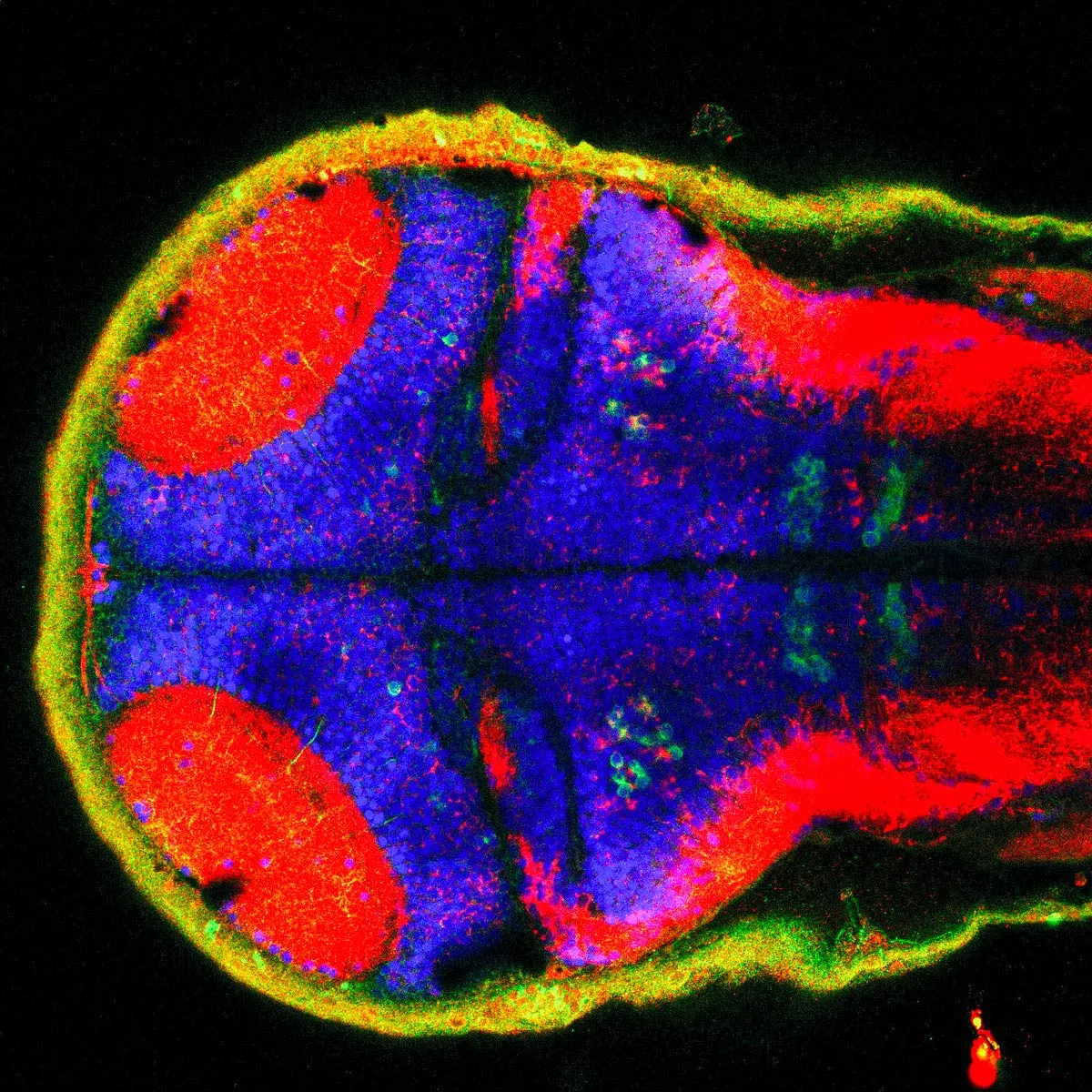

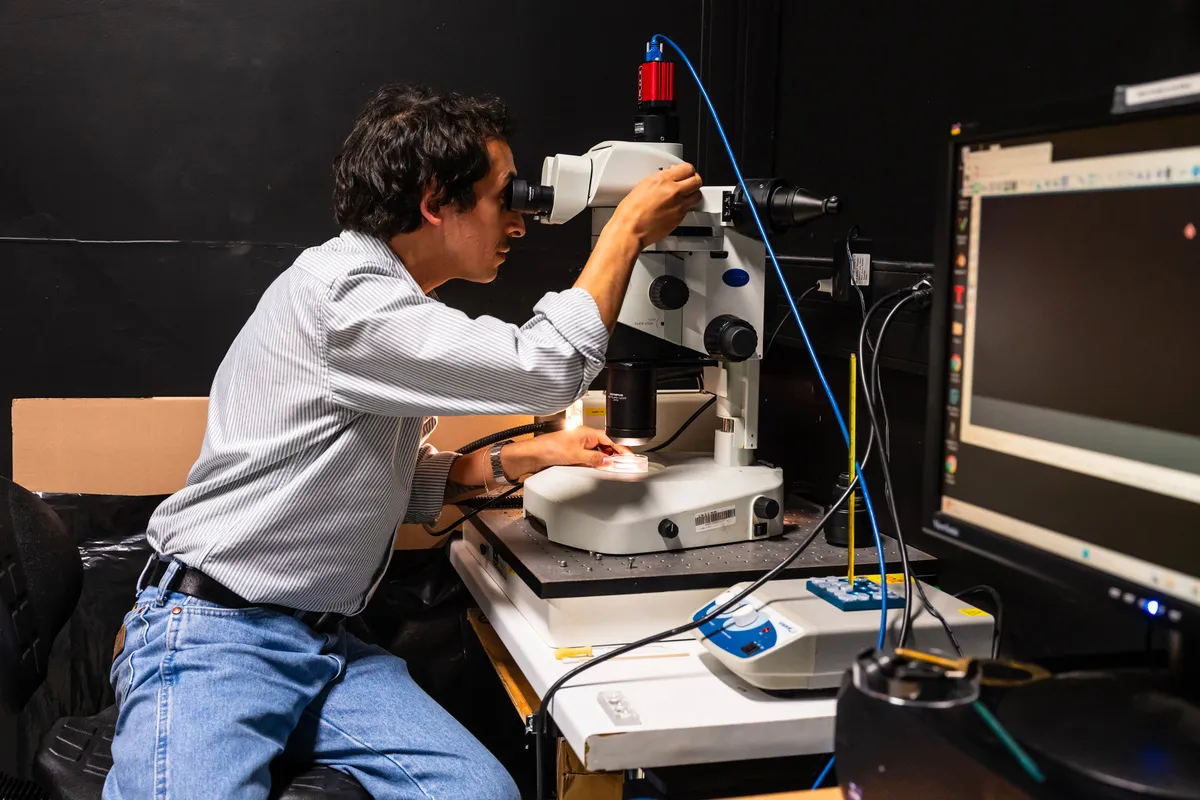

Whole-brain imaging, genetic manipulation, optogenetics, behavioral analysis, virtual reality and mathematical methods for analysing the activity of neural networks are all techniques that will enable the team to dissect in detail the mechanisms underlying the generation of cognitive spatial maps in Astyanax mexicanus variants.

This comparative approach, at the crossroads of neurobiology, behavioral ecology, evolution and cognitive sciences, will provide a better understanding of the mechanisms and principles underlying the evolution of spatial navigation in vertebrates, and open the door to study how neuronal computations adapt to drastic changes in the environment.

Germán Sumbre in a few words

Germán Sumbre is a neurobiologist who completed his doctorate at the Hebrew University of Jerusalem (Israel) and a post-doctoral fellowship at the University of California Berkeley (USA). In 2009, he set up his own team at the Institut de biologie de l'Ecole normale supérieure (IBENS) in Paris.

Since then, his field of study has been neuroethology, which explores animal behavior and the underlying neural mechanisms in vertebrates. His research focuses particularly on the zebrafish (Danio rerio) and more recently the Mexican tetra (Astyanax mexicanus) and the acoustic communication in bottlenose dolphins.